Are you sitting down to write those Christmas cards? Or, have you sent all the cards you're going to send this year?

Either way, have you ever wondered why it is that we send them and who was responsible for sending the very first Christmas card?

In 1979, two Christmas cards, that had been sent to King James 1st and his son, Prince Henry, by German physician Michael Maier (1568–1622), came to light in Scotland. The card's greeting read, "A greeting on the birthday of the Sacred King, to the most worshipful and energetic lord and most eminent James, King of Great Britain and Ireland, and Defender of the true faith, with a gesture of joyful celebration of the Birthday of the Lord, in most joy and fortune, we enter into the new auspicious year 1612."

So, technically, this could be classed as the first Christmas card.

However, this was a personal card and it was never intended for mass circulation.

So, who was it that sent the first commercial Christmas card?

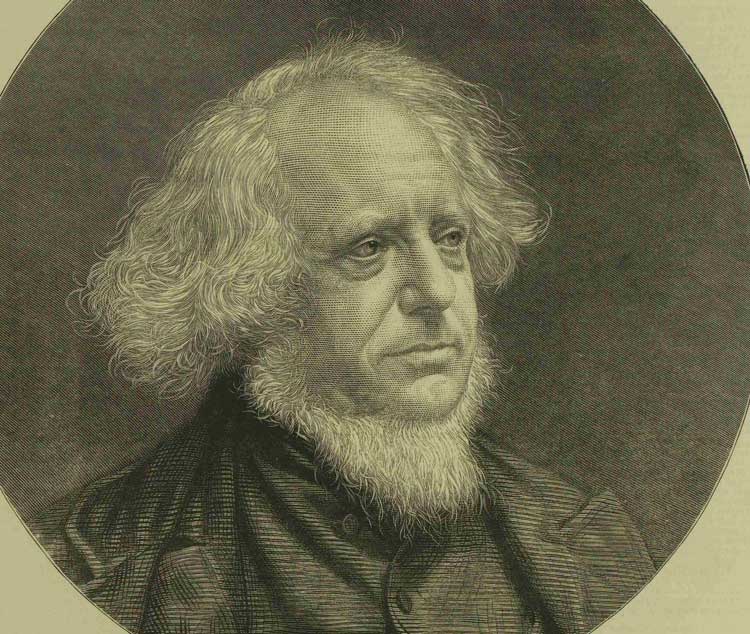

Take a bow Sir Henry Cole, who, in 1843, was working at the Public Records Office, and who was also producing "Felix Summerley's Home Treasury" - an annual children's book that was illustrated with "woodcuts after famous pictures." The book was published by Joseph Cundall from his premises at 12, Old Bond Street, London.

Henry Cole was one of those Victorians who could achieve just about anything he put his mind to.

He had been instrumental in the establishment of the 'penny post' in 1840, having worked as assistant to its main instigator Rowland Hill.

He would go on to become the mastermind behind the Great Exhibition of 1851, his involvement personally requested by Queen Victoria's Consort, Prince Albert, who famously punned that, "if the exhibition is to steam ahead, we must have Cole."

In May, 1843, Henry Cole realised that the postal service could offer a commercial opportunity to enable people to send Christmas messages cheaply and with less hassle than having to hand write dozens, if not hundreds, of letters, each one bearing a personalised Christmas message to family, friends and acquaintances.

Why not just mass produce one message that could be sent out en masse? He thought.

And thus, he approached the artist John Callcott Horsley (1817 - 1903), and commissioned him to design a card that would contain the usual season's greetings and which could then be posted out to eager recipients.

Horsley went to work, and, by December, 1843, he had come up with the prototype for the first commercial Christmas card.

The first cards were printed in lithography by Jobbins of Warwick Court, Holborn, London, and were hand-colored by a professional colourer by the name of Mason.

The cards were published by Joseph Cundall under Sir Henry Cole's nom de plume, "Felix Summerly" and were sold from Cundall's premises in Old Bond Street.

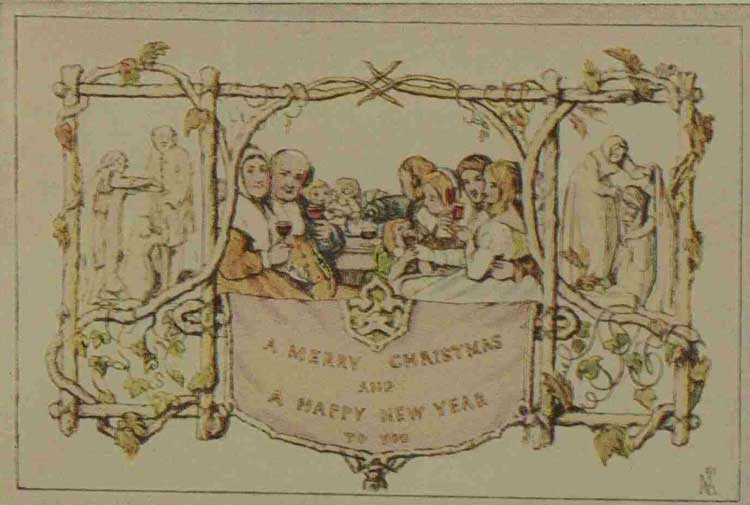

The card itself, as designed by John Callcott Horsley, consisted of three panels.

A central panel showed the Cole family gathered around their Christmas feast raising their brim-full wine glasses to toast the health of the recipient.

Beneath them was the message "A MERRY CHRISTMAS AND A HAPPY NEW YEAR TO YOU."

Two outer panels depicted scenes of charity, with food and clothing being given to the poor.

At the top of the card was the word "To", followed by a space in which to insert the recipients name.

At the foot of the card was the word "From", after which the sender could write their name. A simple and effective method to perform a task that, up until then, had proved somewhat taxing!

However, those very first Christmas cards weren't without controversy.

The fact that the family were drinking wine was, so the advocates of temperance argued, promoting drunkenness.

Also, the image of children drinking - in particular the little girl in the green dress in the foreground of the card who is being given a glass of wine by her elder sister - was considered by many to be totally outrageous.

So the card did attract a certain amount of criticism.

Two batches, totaling 2050 cards, were produced for Christmas 1843.

One version was black and white, and retailed for sixpence, the other was a hand-coloured version that cost one shilling, quite a substantial amount in those days.

Mind you, in recent years, several of those first Victorian Christmas cards have been auctioned and have fetched impressive sums of money.

In 2001 a card, signed and sent by Henry Cole himself and sent to his grandmother and aunt, sold for a record £22,500 at auction in Devizes, Wiltshire.

And, in 2013, a black and white version sent to a Miss Marinda Cundy, London - by a sender who simply signed it J.C.J - went for £4,200.

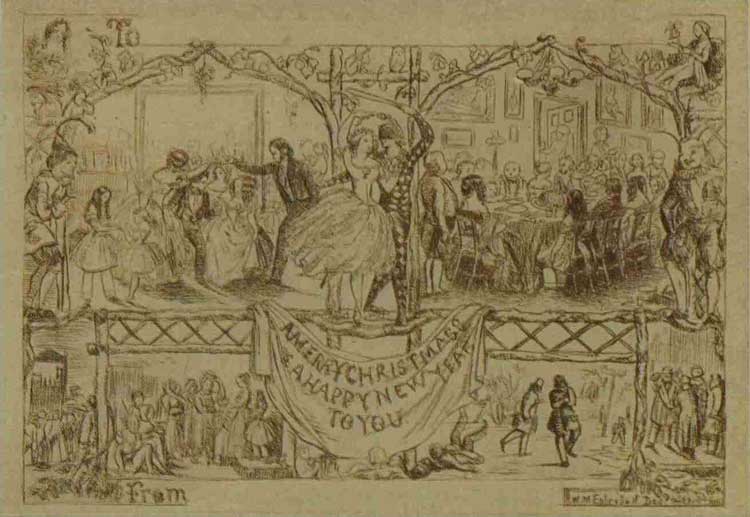

It is noticeable that Cole's time-saving innovation didn't catch on immediately, and it wasn't until 1848 that the second Christmas card - designed by the artist William Maw Egley (1826 – 1916) - arrived on the scene.

Just like its predecessor, this card also showed middle-class festive merry-making, alongside acts of charitable giving.

However, these early cards were considered quite expensive at the time, and the custom of Christmas card sending didn't really begin to take off until the mid-1850s.

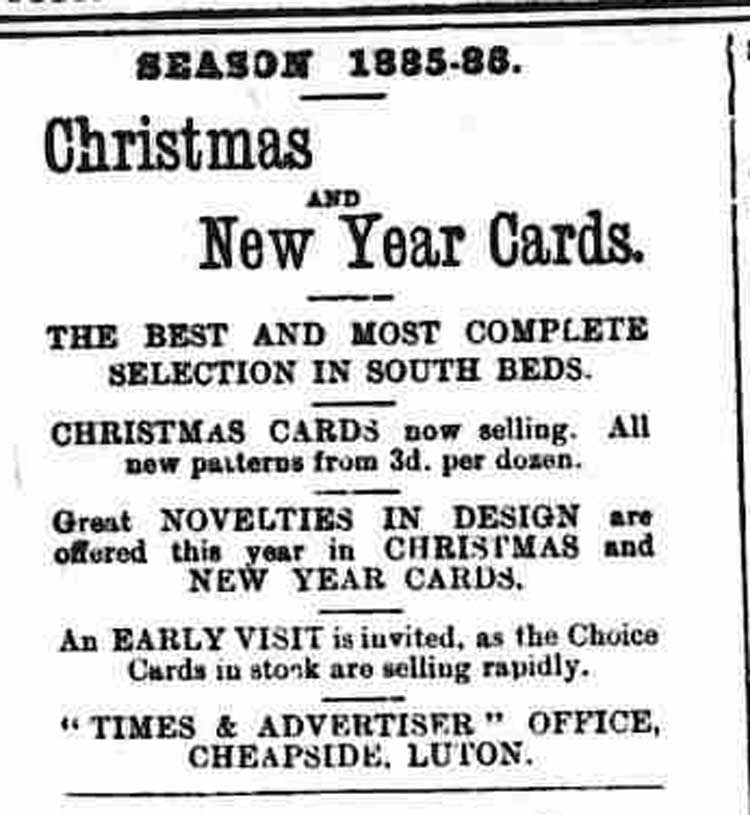

It was in 1855 that adverts for Christmas cards began appearing in the newspapers, such as the one below, which appeared in The Luton Times and Advertiser on Tuesday, 4th December, 1855.

These early Christmas cards featured embossed and pierced paper, as well as layers that could be opened to reveal flowers and religious symbols, such as angels watching over sleeping children.

However, as printing presses became more and more technologically advanced, during the second half of the 19th century, more extravagantly detailed cards were produced, in ever increasing numbers; and when, in the 1870s, the cost of sending a card decreased, their popularity increased dramatically, and more and more Christmas Cards were being sent throughout the 1870s and 1880s, ushering in the heyday of the Victorian Christmas card.

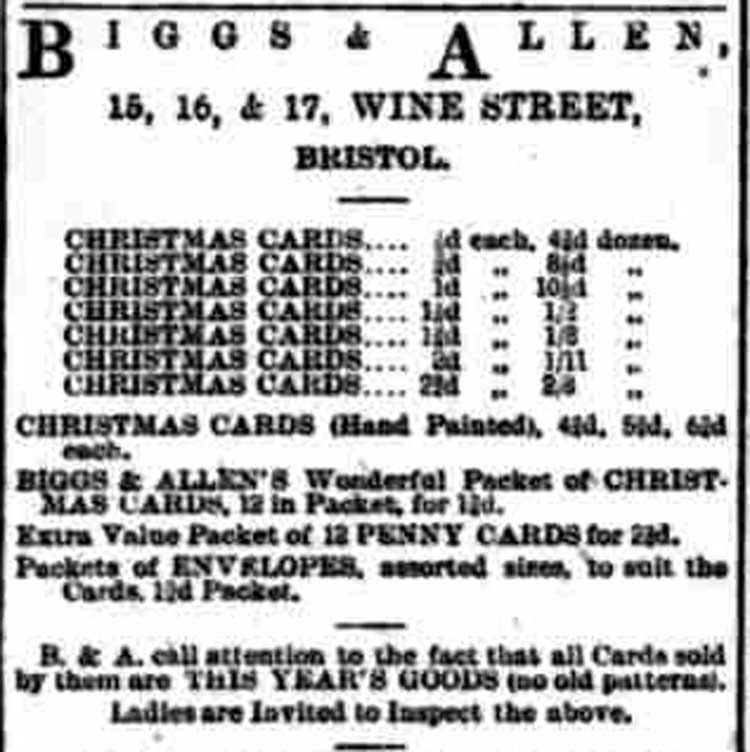

The following advert appeared in 1889, and evidently it was felt hugely important to make it abundantly clear that the shop in question wasn't trying to palm off unsold stock from previous years on its customers, as the advert pledged that, "...all cards sold by them are THIS YEAR'S GOODS (no old patterns)."

From The Bristol Times and Mirror, Saturday, 7th December, 1889.

Copyright, The British Library Board.

The scenes depicted on these cards included religious symbolism, the ever popular subject of children preparing for or enjoying Christmas, and all sorts of winter landscapes, such as snowy villages, country churches and people walking, red-faced and jolly, across snow-covered fields or through icy city streets.

In so doing, these cards helped establish a popular image of what Christmas should look like, and that image is still with us to this day - I bet you're dreaming of a white Christmas!

Interestingly, from the the 1870s onwards, a popular image on Christmas cards was that of a red-robed Father Christmas, who was often shown trudging through the snow with a sack full of presents slung over his shoulder.

This somewhat contradicts the common fallacy that Coca-Cola started the tradition of dressing Santa in red as part of an advertising campaign.

In fact, Coca-Cola didn't start using Santa in their adverts until 1933, whereas he had been appearing, dressed in red, on Christmas cards since the 1870s - and, thus attired, images of him had been appearing since the early 19th century.

So, when you're sitting at your Christmas luncheon, and Neil, the know-it-all from the finance department, decides to show off his knowledge by cynically telling everyone that it was Coca-Cola who had the idea of dressing Santa in red, just turn to him and snap, "Bah! Humbug!"

Robins were, and remain, a popular subject on Christmas cards.

A popular fable held that when the baby Jesus was in his manger, the fire, which had been lit to keep him warm, began to blaze ferociously. A brown robin promptly fluffed out its feathers to protect the baby, and, in so-doing, its breast was scorched by the fire, and the redness was then passed on to future generations of robins.

Some say this is why the robin began to appear on Christmas cards.

However, there may have been another reason why the robin became synonymous with Christmas on cards.

Early Victorian postmen used to wear red frock-coats - red being the colour of Royalty - and postmen were, in consequence, nick-named "robins."

Some of the early cards depicted robins - to represent postmen - delivering cards with their beaks, and the robin duly became a popular figure on Christmas cards.

Indeed, on some of the later cards, the robin would be shown with a satchel filled with Christmas cards hung over its wing.

So, by the 1890's the Christmas card industry was well and truly established, and it has continued to - if you'll pardon the expression - snowball ever since.

Indeed, according to the Greeting Card Association, the total number of single Christmas cards sold in the UK in 2018 stood at 100 million, plus a further 900 million sold in boxes or packs.

And, to think, it all started because Henry Cole decided to save himself some time, and an awful lot of effort, at Christmas in 1843.

Neil, the know-it-all from the finance department, is a fictional character created for the purposes of this article, and is not meant to be a reference to an actual person. Richard Jones would like to apologise to any Neil, who works in a finance department, for any inconvenience the use of his name might cause at the Christmas luncheon. Unless, that is, you have just told your colleagues that Coca Cola dressed Santa in red.