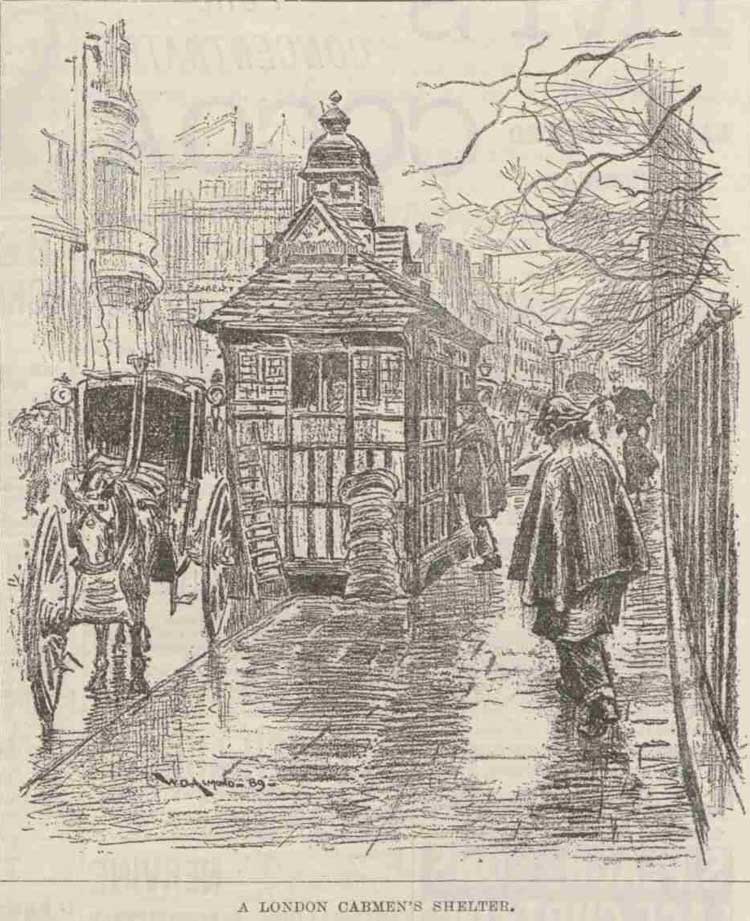

Scattered throughout the streets of London you will find thirteen little green huts or sheds that are the preserve of the capital's black-cab drivers. They are, in fact, Cabmen's Shelters, and inside these little havens London's cabbies can relax and enjoy steaming mugs of tea and coffee, as well as filling plates of hot food.

To trace the origins and history of the Cabmen's Shelters, it is necessary to head back to the late 1860s and early 1870s, when heated vehicles and tight turning circles were luxuries that a London cabby could not have even begun to dream of.

A cabby's working environment was a harsh and unforgiving one.

It consisted of being perched over his cab in all weathers, and in London, particularly in the winter months, that meant in choking fog, lashing rain, clothes-dampening drizzle, biting wind or freezing snow.

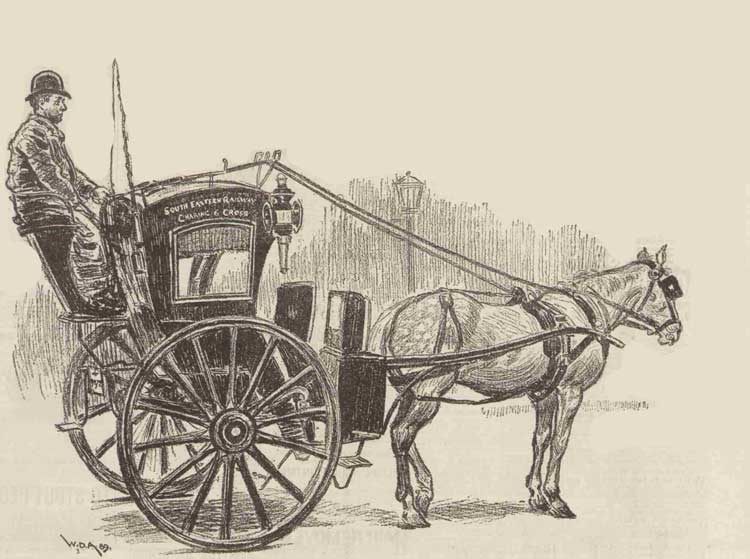

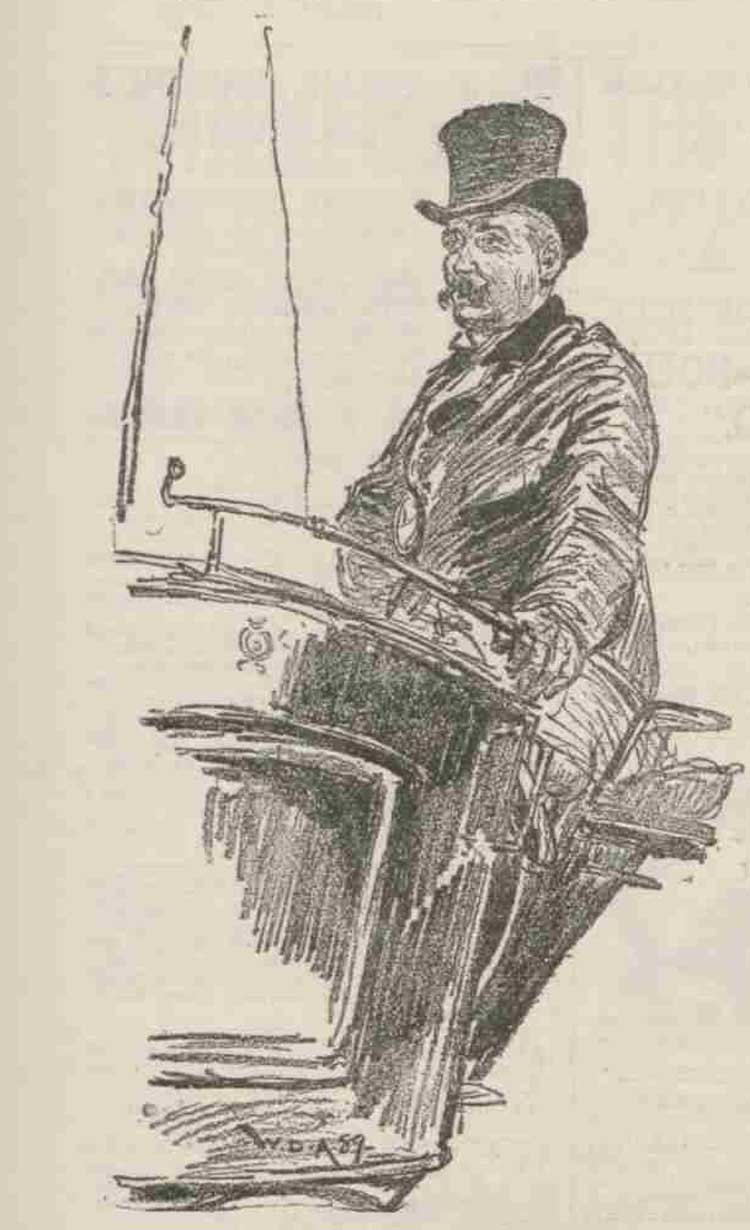

A Victorian Cabby

When parked up at the cabstand, a cabby was not allowed to leave his vehicle unattended, and, if he were to head to a pub to get some food and use the facilities, he would have to pay somebody to mind his cab, or else run the risk of having his cab - and, therefore, his livelihood - stolen.

Many cabbies, however, did look to London's pubs to provide for their needs corporal; and, as you can imagine, cab-driving and alcohol did not make for easy bedfellows, nor, for that matter, for a particularly safe journey for the fare-paying passenger or for passing pedestrians, as is evidenced by the following case that was heard at Lambeth Police Court and which was reported by Reynolds's Weekly Newspaper, on Sunday 22nd November, 1874:-

"John William Feagus, a cabdriver, badge 552, was charged with being drunk with a horse and cab, and with doing some bodily harm to an old woman.

The complainant said that she was knocked down by a cab, and the driver went away "like lightning."

According to the evidence, the prisoner was drunk, as was also the woman, who, it appeared, fell up against the cab as she was crossing from Oakley-street.

One of the witnesses said that the prisoner was going at the rate of about fourteen miles an hour; another said it was about seven miles an hour.

The police-constable said that the cab driver was drunk, and could not stand when he got off his cab.

The prisoner denied that he was drunk, and also that he was driving at a furious rate.

Mr. Chance had no doubt that had the prisoner been sober the accident would not have occurred, and it was through the old woman being drunk that she fell down.

The case might have been more serious than it was now proved to be; it was, however, one that could not be passed over. To be drunk while in charge of a horse and cab was an offence to be checked. He fined the prisoner forty shillings and in default of payment one month's hard labour."

In 1872, a prototype of the Cabman's Shelter opened its doors in Knightsbridge, and The Graphic praised its advantages in the following article, which appeared on Saturday, 20th January, 1872:-

"Some philanthropic gentlemen have kindly taken in hand the task of making the lives of our cabmen a little less unendurable and, by way of commencement, have opened a model refreshment house near an important cabstand at Knightsbridge.

It has, in fact, occurred to these gentlemen that cabmen, like those who ride in cabs, do occasionally require some support in the way of food and drink, and that to expect them to be in all weathers seated upon the box from morning to night, is un reasonable.

The fact is that, let the regulations be what they will, drivers must occasionally leave their vehicles and this being the case, it is certainly better to recognise the practice, and to make some provision for carrying it out without danger to the public.

Generally, the appointed attendant at the stand would be quite capable of guarding for a short time, even, one or two cabs so left and a trifling fee to him might be permitted. Cabmen are, after all, not much worse than the average of human nature.

They sometimes, it is true, form an exaggerated estimate of the sum they are going to receive from a passenger, and are apt to be disappointed, and to give vent to their feelings when dismissed with what they call "bare fare."

But this is a peculiarity of most classes whose reward is uncertain, as it necessarily must be with cabmen, while some fares are as unnecessarily generous, as others are severely economical and there is certainly some excuse for them in the fact that cabmasters are well aware of the custom of pour boires and extra six pences, and regulate their demands on the men accordingly.

Any way, there is no harm in trying a little kindness with the cabdrivers.

Perhaps in time even the rudest members of the class may be ashamed to bully the public when they find the public not indisposed to treat them with more humanity and consideration."

From The Penny Illustrated Paper Saturday, 25th April, 1891.

Copyright, The British Library Board.

However, with somewhere in the region of 7,000 cabmen trotting about the streets of the Victorian Metropolis, one refreshment house in Knightsbridge was nowhere near sufficient, and, on Saturday, 11th October, 1873, The Globe suggested the necessity of adequate shelter for the cabmen:-

"Cabmen have a good many weak points, but they are very useful public servants; and it is too bad that, in addition to the unavoidable hardships and discomforts of their occupation when actually at work, they should be compelled to stand exposed to all sorts of weather, or else spend no inconsiderable portion of their earnings in the public house.

If it could be clearly ascertained how many of them fall into habits of drunkenness, or become victims of disease long before they have attained the time of life at which they ought to be at their prime, the public would be considerably startled, and perhaps a little conscience-smitten.

A very small outlay would be sufficient to provide every cab-rank with such a shelter for the men engaged on it as would add immeasurably to their health and comfort.

The present season is very suitable for directing public attention to the subject.

Any philanthropist who will take the matter in hand, and agitate until he succeeds, will not only have the satisfaction of having done a work of real benevolence, but will secure the hearty gratitude of many thousands of hard-working, hard-faring men."

In early 1874, The Globe began campaigning in earnest to establish shelters in which cabmen could enjoy a little respite between journeys, and, on Friday, 2nd January, 1874, it published the following article revealing that the Metropolitan Police Commissioner would have no major objection to such shelters:-

"The subject of providing "cabmen's rests" for the purpose of supplying a place of shelter to the drivers upon the stands, having been brought before Colonel Henderson, he has replied that the statutory powers possessed by him of appointing stands for hackney carriages do not extend to the proposed erections.

While, however, he cannot either authorise or sanction them, he is advised that no duty is thrown upon him of proceeding against those who erect such places."

Whereas The Globe became the campaigning newspaper on the need to offer some form of shelter for London's cabmen, the Pall Mall Gazette became the newspaper that sought to highlight the dangers posed to the public by drunken cabmen, whilst, at the same time, being highly critical of the lenient sentences that were handed out to drunken cab drivers by magistrates.

On Saturday, 25th April, 1874, the Gazette published the following article:-

"Good Samaritans are, no doubt, entitled to the utmost respect, but there may be too much of a good thing, and even the goodness of a Samaritan, unless tempered with discretion, is apt to produce serious results.

An example of this is afforded by an interesting case which came before the magistrate at Hammersmith police-court yesterday.

William Carter, a cabdriver, and Mr. Bell, a gentleman, were charged - the cabman with being drunk during his employment, and the gentleman with furious driving.

It seems that on Thursday evening a police-constable on duty in the Lillie-road, Fulham, saw a hansom cab, driven by Mr. Bell, proceeding at the rate of sixteen miles an hour.

The constable called to Mr. Bell to stop. No notice was, however, taken of this request, but a voice from inside the cab shouted "Go on." Mr. Bell did "go on" -he also went "off," for, on turning the corner of the street, he was thrown from the box, and the vehicle was stopped by the constable.

The mystery of "the voice" was then cleared up, for inside the cab, comfortably reposing on the cushions was the cabman Carter, holding one rein in his hand, and overcome by drink.

Mr. Bell, by his own account, had seen Carter, whom he knew, in a public-house in this painful condition, and from motives of kindness proceeded to drive him home, when the horse bolted and the catastrophe witnessed by the constable occurred.

He had, according to his solicitor, merely acted the part of "a good Samaritan."

The magistrate, however, sentenced each prisoner to pay a fine of twenty shillings, or in default to suffer fourteen days captivity; nor can this penalty be considered severe, for if good Samaritans drive drunken cabmen home at a furious rate they will soon become objects of dread instead of admiration."

Warming to its theme of highlighting the excesses demonstrated by some of London's cabmen, the Gazette published the following article in its edition of Saturday, 15th September, 1874:-

"It is a poor compliment to dumb animals that any display of intelligence on their part is always recorded as a singular fact, and as though they did not frequently show that they possess mere common-sense that many human creatures might well envy.

A remarkable instance of the intellectual capacity of "brute beasts" (as they are termed) is afforded by the conduct of the London cab-horses.

Seldom or never do these praiseworthy animals knock down and run over any one unless compelled to do so by their drivers; yet, considering the number of drunken cabmen who are now almost daily brought before the magistrates, each with his licence marked over and over again for the same offence, an immense temptation must be thrown in the way of the cab-horses to run riot through the streets of London.

Only yesterday, at the Westminster police-court, it appeared by the evidence given in the case of a cabman named Brierly, charged with being drunk and incapable during his employment as a driver, that while Brierly was sleeping the sleep of the intemperate on the pavement in Keppel-street, Chelsea, surrounded by a crowd of sympathizers, his horse was quietly waiting with the cab in the carriage road until Brierly awakened to sobriety.

Long might the horse have waited for that auspicious moment but for the arrival of a police-constable, who tenderly deposited Brierly in his own cab, and with the help of the horse conveyed the precious burden to the police-station.

Brierly was fined nine shillings, or in default sentenced to seven days imprisonment, and some portion of this penalty might with propriety have been awarded to the horse, who well deserved an extra feed of corn for not whiling away the dreary hours of Brierly's slumber by causing a few street accidents."

Towards the end of 1874, The Globe's campaign enjoyed a flurry of activity, and it began to report, almost daily, on the movement to provide adequate shelter for London's cabdrivers.

In its issue of Friday, 10th December, 1874. The Globe made the following appeal:-

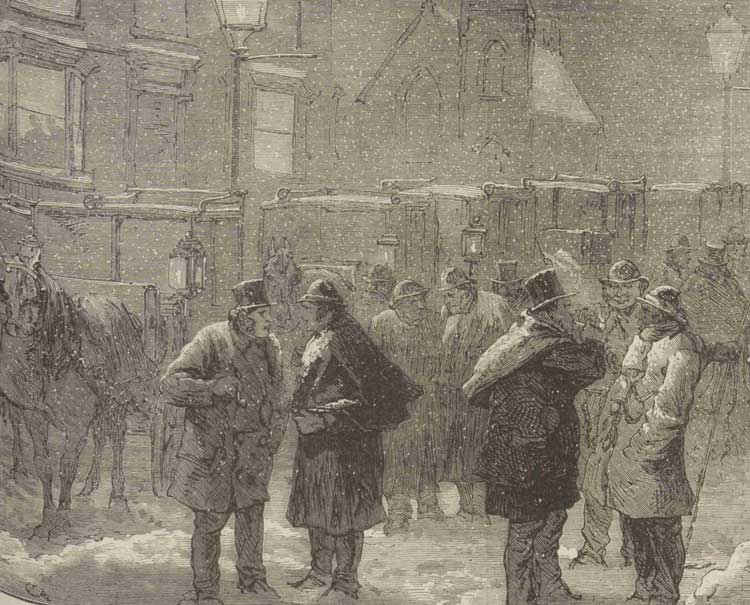

"We have repeatedly called attention to the need for some sort of shelter for cabmen in winter.

The cold weather that has now set in once more suggests the subject.

Everyone is familiar with the wretched appearance of poor "cabby" while waiting patiently for a fare, or in vain attempting to transform some passer-by into that profitable commodity.

He stamps on the pavement, exchanges doleful jokes with his fellows, or, if he has not sufficient energy for these exercises, sits shivering and apparently meditating on the unsympathetic universe.

When the time for a meal arrives, his food is neither hot nor cold, and it but slightly cheers him.

His ills are, of course, tenfold increased at night, when there is probably a miserable fog, or it rains or freezes.

No wonder that the unfortunate man, when a fare at last appears, makes the most of his opportunity, or has frequent recourse to the nearest public house for "refreshment."

He notoriously drinks far too often more than is good for him - certainly more than he can afford to pay for if he considers the wants of his wife and children.

A very simple remedy for this state of things might be found in some such shelters as those already supplied in a few of the great provincial towns.

An excellent building of this sort has been erected in Birmingham; and the correspondent of a Manchester newspaper, who urges that the example should be followed in the latter city, says he has often observed how comfortable the men appear in their "pretty looking home."

They can prepare tea and coffee at a pleasant fire, and bandy their favourite jokes without their teeth chattering from the effort.

It seems that a shelter costs only about £l5O. Surely there are many philanthropic people who would willingly incur this expense if the matter were fairly brought before then.

Religious meetings are held for the special benefit of cabmen; they are also frequently presented with tracts.

Will not someone take means to protect them from the bitter cold?

After all, although their exorbitant demands are sometimes irritating enough, they are both a useful and good-humoured class of men, and deserve to be made as comfortable as circumstances sill permit."

Cabbies On A Cabstand In The Snow

In its next day's edition - Friday, 11th December 1874 - the newspaper published the following letter from a reader who saw the benefits of the establishment of such shelters, and who, more importantly, was more than willing to put his money where his mouth was:-

"I have been much impressed with your "Note of the Day" on "Cabmen's Shelters."

No one who has been about at night can have felt anything but pity for the poor fellows on the stands of London.

The "shelters" you advocate would not only benefit the cabmen, but the public as well, for what can be more disagreeable than to enter a cab in which the driver has been sleeping for some time, with, in most cases, all the windows up?

I believe that some time ago a "shelter" of this sort was contemplated at Sloane-street, but the idea was given up in consequence of Colonel Henderson's opinion being against the legality of the structure.

Surely this difficulty might be overcome?

A great deal is said about London "cabbies," but, taken as a class - and I speak from experience - they are the most civil and obliging set of men of their profession in Europe.

A great deal has been done to improve the position of labouring men, but "cabbies" have been left out "in the cold," to say nothing of the "wet."

I hope your influence may enable them to get at least one "shelter" established.

I believe the top of Sloane-street would be a good place to experimentalise upon, but I leave details to abler hands.

You estimate the cost of a "shelter" at £l5O. I shall be most happy to send you a cheque for £25 as soon as £125 is subscribed towards this most desirable object.

I am, Sir, your obedient servant, C. A. 0. December 10."

"We trust the generous challenge of our correspondent may be responded to. ED. The Globe."

The Globe had, by this time, well and truly embraced its theme, and, on Saturday, 12th December, 1874, it published the following article highlighting how such a scheme might work in London:-

"We called attention the other day to the urgent need, now that cold weather has fairly set in, for providing what are conveniently called "shelters" for cabmen.

One such structure could, we believe, be raised for £l5O.

A correspondent, whose letter we published yesterday, not only thinks a shelter should at once be set up as an experiment, but generously offers to send £25 "as soon as £125 is subscribed towards this most desirable object."

We beg to thank this gentleman for his prompt response to our appeal, and sincerely hope others may come forward and help to raise the necessary sum.

The desirableness of each buildings as we have described is so obvious that we are sure the subject has only to be brought under the notice of the public to be at once attended to.

In summer "cabby" has, perhaps, no more hardships than he is able to bear; but in winter the state of the case is very different. He has to pass many weary hours in cold and rain, having no means except recourse to the public-house of fortifying his courage; and we fear many a poor fellow is driven by sheer necessity to drink quantities of gin and whisky that in the long run ruin his health, and greatly limit the comforts of his wife and children.

If a shelter were provided, in which he could always have a bright fire and a cup of tea or coffee when he chose, half the temptations which now assail him to drink to excess would be removed.

The public would benefit almost as much as cabmen, for, as our correspondent urges, "what can be more disagreeable than to enter a cab in which the driver has been sleeping for some time, with, in most cases, all the windows up?"

We may add that a cabman whose physical wants are fairly looked after will not be nearly so apt to add an extra sixpence to his charge as one who feels he must compensate himself for his sufferings.

It may be suggested that there would be difficulty in calling a cab at a stand if the scheme were carried out.

At Birmingham, where a shelter exists, each cabman stands in turn outside as a sentinel, so that no inconvenience arises.

Surely at this time of the year, when so many are in a genial state of mind, and the poorest are made happy by seasonable gifts, a few kind-hearted people will be willing to make a slight sacrifice for a deserving class of men.

We have often thrown out hints to cabs men as to some of their little foibles, but it must be admitted that on the whole they display singular patience, courtesy, and good humour in their rather trying calling.

And a contrivance which they highly value in Birmingham is not likely to be less highly valued in London."

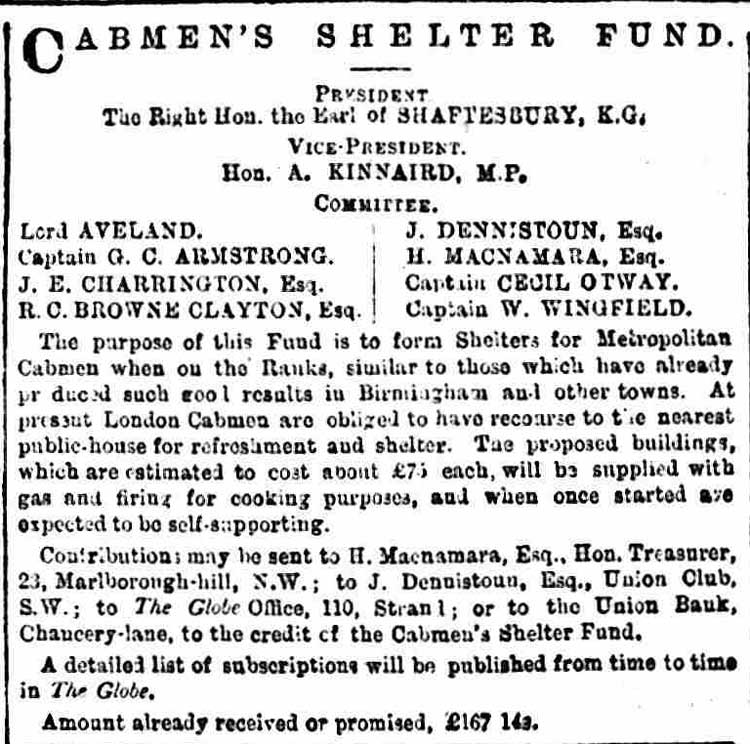

Within days, donations were being offered by various readers of The Globe and, by the 19th December, 1874, £100 had been pledged by readers; and the newspaper was able to report the setting up of the "Cabmen's Shelter Fund", with the Earl of Shaftesbury as its president.

By 23rd December, 1874, the amount donated had risen dramatically.

On that day, the "Cabmen's Shelter Fund" published the first of a series of adverts in The Globe soliciting further contributions:-

From The Globe 23rd December, 1874.

In that same day's edition, The Globe pointed out how useful London's cabmen were at that time of the year, and extolled the virtues of the newly established Fund:-

"The charioteer of Father Christmas is obviously the cabman.

The pantomime, the ball, the family gathering, would fare but badly without his assistance in bringing up the flocks of pious observers of the season.

Even when a brougham is available, the wise paterfamilias prefers to save his horses from the terrors of the rough and slippery streets, and prudently packs his Christmas expedition in a cab.

But when every one has been safely taken to the homes of some one else, what becomes of the indispensable cabman until it is time to take every one home again? He must wait out of doors with his blue fingers to his lips, or his arms flapping against the breast of his great coat, or else he must go into a public house and pay for the privilege of warming himself by buying "something to drink", which he does not want.

Fortunately, things seem about to take a turn very much in the cabman's favour.

We published yesterday a letter from Mr. Macnamara, the railway Commissioner, calling attention to the institution of cabmen's "shelters".

It has been proposed by this gentleman and other benevolently-minded persons to establish at suitable points places of meeting for cabmen, where they may obtain protection from the weather, and, if they like, take their meals.

At Birmingham and elsewhere in the country "shelters" of this kind have been most successful, and a payment of 6d a week by each cabman using the "shelter" has been found sufficient to make them almost self-supporting.

The funds necessary to start the movement we do not think will be wanting when the world is made aware of so simple and admirable a scheme for increasing the comfort of the faithful public servant who, at a pinch, is everybody's coachman."

By the end of the 1874, the fund had reached more than £200; sufficient to commission the construction of the first Cabmen's Shelter, which opened in Acacia Road, St. John's Wood on Saturday, 6th February, 1875.

The Graphic, which had done so much to promote the fund and the shelters, wondered why it had taken so long for such a necessity to be provided for the Capital's hard-pressed cabbies in the following article which was published that day:-

"It is not a little singular that London, the metropolis of the three kingdoms, should often be so far behind some of the provincial towns in matters relating to social improvement and the physical and mental well-being of the working classes. Free Libraries, Mechanics Institutes, Working Men's Clubs, the Co-operative System, and even Hospital Sunday, were all originated outside the twelve-mile circle, and some of these, even when admitted within it, have not flourished so vigorously as they do in the places where they were at first established.

The Cabmen's Shelter movement is a case in point.

These invaluable conveniences have been adopted for some time in Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds, Glasgow, Edinburgh, and various other towns, and no doubt appears to exist as to their practical value, and the appreciation with which they are regarded by the men whom they are especially intended to benefit.

And now London, "the rainiest city in Europe," has suddenly awakened to the fact that it would be better for her cabmen to await their fares in a comfortable apartment close to the cab rank, than to stand about in the soaking rain, or at the bar of the nearest tavern.

The London Cabmen's Shelter Fund has been established by a number of gentlemen under the presidency of the Earl of Shaftesbury, whose name is connected with so many noble and charitable works, and the first shelter, which will be opened today by the Hon. A. Kinnaird, M.P., Vice President of the Fund, is to be placed in Acacia Road, St. John's Wood.

Others will be placed in various parts of the metropolis as soon as sites can be obtained, and the necessary funds are forthcoming.

Each structure will be about seventeen feet by six feet, and ten feet six inches high, will run on low wheels, and be made on the model of those in use at Birmingham and elsewhere.

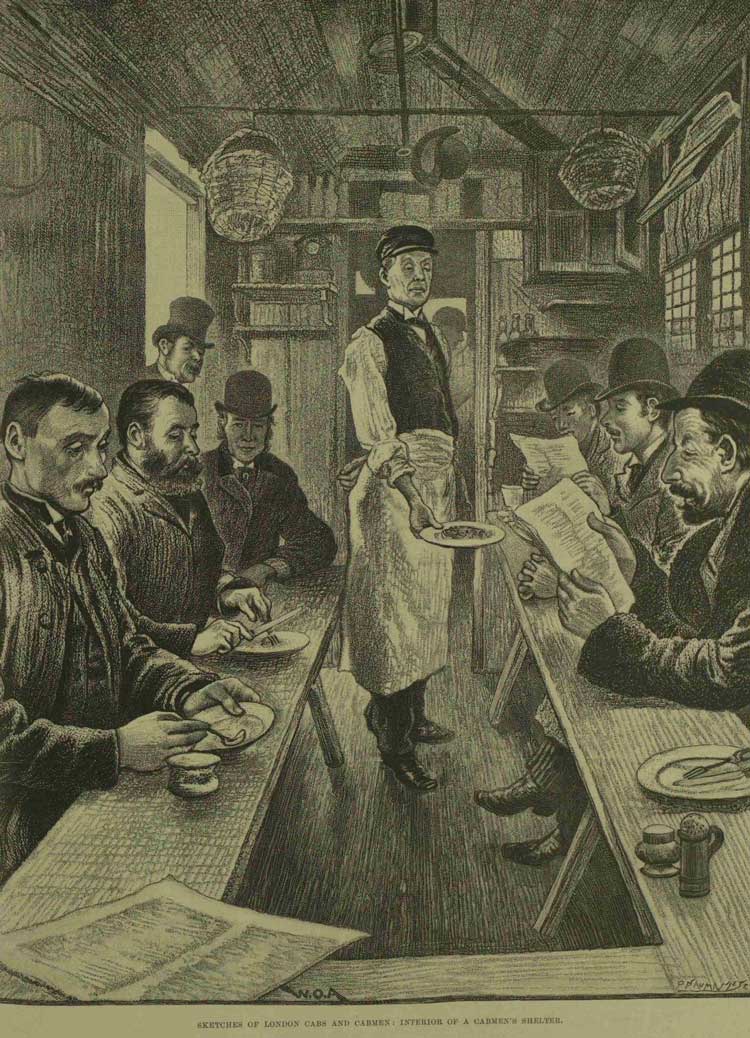

They will be supplied with light, water, and a stove for cooking, and will be under the charge of an attendant, who will supply tea, coffee, &c. at fixed rates to those who use the shelter, and whose duty it will be to preserve order.

The payment of one penny per day, or fourpence per week, will secure the right to use any and every shelter in London, and it is intended that eventually they shall all be open continuously day and night, though for the present the one in Acacia Road will only be available from 8 A.M. to 12 P.M.

The benefits, both physical and moral, which the hard-working and much-abused cab-drivers are likely to derive from an effort of this kind, are so self-evident that we need not enumerate them."

From The Penny Illustrated Paper Saturday, 25th April, 1891.

Copyright, The British Library Board.

By April, 1875, nine shelters had opened, and, as the following article, which was published in The Globe on Wednesday, 28th April, 1875, made clear, there was no doubt as to their usefulness:-

"The perfect success of the movement for providing metropolitan cabmen with shelter against inclement weather no longer remains open to doubt. Wherever the refuges have been erected, there is but one opinion as to their extreme utility. In fact, the only cause for wonder seems to be that such a crying want remained so long unsatisfied.

At present, no less than nine shelters are in full operation. Of these, those at Acacia-road, Harrow-road, Langham-place, Davies-street, Knightsbridge, South Kensington Museum, and St. Clement Danes, are kept open night and day, only the two at St. Peter's, Eaton-square, and at the George Inn, Hampstead, being closed at night.

So much then far work already accomplished, which affords convincing proof of the energy devoted by the committee to the discharge of their self imposed task.

But their labours do not rest here.

At the present time, eight shelters are in course of construction for Sloane-square, Piccadilly - at the bottom of Clarges-street - St. James's-street, the Houses of Parliament, Brecknock-road, Southwark-street, Borough, and Park-place, St. John's-wood.

When these are completed and placed in the course of the next month, London will possess seventeen shelters in full working order, although it seems only the other day that the movement was inaugurated.

In view, of this rapid progress, it is no longer possible to doubt these shelters meet a public want which has been only too long neglected, and that they ought to be extended to every part of the metropolis.

But, to do this, additional funds are needed, the amount already subscribed being nearly expended, so that unless the public come forward, the movement must halt when its work is not one-tenth part accomplished.

It should be remembered that, although the shelters are not so much required in summer as in winter, the need of funds remains the same as during the cold weather.

If the principal cabstands of the metropolis are to possess shelters next winter, the latter must be constructed during the present summer, since they take some time in building.

But, before giving orders for the number required, the committee must have money in hand to pay for them, and this can only come from the public.

We have less hesitation in urging this matter inasmuch as we were identified with the movement from its commencement, and therefore feel in some degree compelled to aid the committee in their praiseworthy labours.

It must be remembered that until the number of shelters is largely increased the financial part of the management must labour under great difficulties.

Each penny ticket giving admission for the day to every shelter in London, the greater the number of such refuges, the greater will be the inducement to purchase tickets.

At present, many cabmen abstain from doing so, fearing that after their first fare they may not chance to take up position on a stand possessing a shelter."

By November, 1877, the movement had proved a huge success, and there was even talk of the Cabmen's Shelters doing something that generations of cab drivers are rumoured to be loathe to do - venture south of the River.

The Globe, on Monday, 12th November, 1877, reported that:-.

"As usual, in the present season, we are in the receipt of many appeals, all more or less deserving, for charitable assistance, but considerations of space compel us to give insertion only to those which appear the most urgent.

Among these, that for the Cabmen's Shelter Fund takes leading place, especially as the movement was started in the metropolis at our recommendation.

In every respect it has fulfilled the favourable anticipations then expressed, the cabmen being unanimous in considering these refuges a great boon to their class.

Its failure in some provincial towns does not conflict with this view, as the conditions governing the daily lives of cabmen are very different in small centres of population from what they are here.

A London cabby rarely returns home during working hours, and must, therefore, take his refreshment where he can get it.

When no shelters existed in London, the only place was the public-house, where, of course, he had to buy something to drink whether he wanted or not.

In a small provincial town, on the contrary, a cabby generally goes home for his midday meal, and is, therefore, in a much more independent position.

Putting aside, however, the benefits thus accruing to a deserving and very hard-working class of public servants, the whole cab-employing community have a direct interest in aiding the movement. It helps to keep the men sober, and every shelter forms a sort of rallying point, where cabs are sure to be found when wanted.

Another public advantage is that anyone requiring cab to attend his house can give the order to the waterman, or attendant in charge of a shelter, with full assurance of its prompt execution.

About half the shelters in London were the gifts of separate individuals who, now that the movement has become entirely self-supporting, have the satisfaction of feeling that, for an expenditure of about £100, a lasting benefit has been conferred on the cabmen of the metropolis.

In a prodigiously wealthy community like that of London, there must be many persons who could well afford this small sum for a purpose which, after practical test for three years, is proved to produce the best results.

We trust that, before many months elapse, the committee will be in a position to place a few shelters at the east and south of London, where they are much needed."

The London Daily News, on Tuesday, 1st January, 1884, reported that the thirty-third shelter had been opened the previous afternoon in St James's Square:-

"Yesterday afternoon the thirty-third shelter provided for Metropolitan cabmen was opened by the Bishop of London. It is situated in St. James's-square, and its cost (£150) has been entirely collected by Miss Jackson, one of the Bishop's daughters.

Dr. Jackson, in declaring the shelter open, stated that the entire sum needed was readily contributed by residents in the square, liberal donations having been given by the Duke of Norfolk, the Earl of Derby, Earl Cowper, Lord Tollemeche, and other inhabitants of the Square.

His daughter, observing from the windows of his house the severe exposure to which cabmen on the stand in the square were subjected in inclement weather, was desirous that there should be a shelter erected there similar to those placed in other parts of London, and, setting herself to work she found no difficulty in raising the necessary funds.

His lordship expressed his hearty approval of such shelters in affording cabmen much needed warmth and wholesome food and drink.

They were especially a boon to those who did not want to patronise the public-house. He believed that cabmen were not more but rather less addicted to drinking than other working people, because excessive drinking to a cabman when at work meant the loss of is license - and perhaps ruin. The cabman who drank excessively would in all probability soon cease to be a driver.

Many men could take their victuals at a public-house with a glass of beer - and he had not the least objection to their doing so - without any risk at all, but to others the very atmosphere and smell of a tavern were an irresistible temptation to excessive indulgence. Hence the advantage of such places as cabmen's shelters, where the weak could have their meals free from this danger at any rate.

Although not personally a total abstainer, he respected those who abstained from intoxicating drinks because they considered in their own interests it was necessary to do so, or because they felt it to be their duty to set an example to others; and he was pleased to find there were many teetotal or temperate cab-drivers who thoroughly appreciated and gladly welcomed the provision of such accommodation as that shelter afforded, which entirely relieved them of any necessity of having recourse to the public-house for their meals.

There had not been the slightest reason to find fault with the conduct of the drivers stationed in St. James's-square.

He concluded by expressing the hope that success might attend the shelter there.

Mr. W. H. Macnamara moved a vote of thanks to the bishop, and to his daughter for her kind and successful efforts in the interests of the drivers.

This was seconded by Mr. Sawyer, a driver, who said the public had conferred no greater boon on cabmen than in providing them with these shelters, which they extensively used and highly appreciated."

By the dawn of the 20th century, close on sixty shelters had been erected across London, and some of them were proving popular with late-night London revelers, as well as with cabmen.

On Saturday, 20th April, 1907, The Morning Post reported that Westminster Council had decided to clamp down on unauthorised members of the public making use of the shelters:-

"The decision of the Westminster City Council to restrict the use of cabmen's shelters within their jurisdiction to cabmen only will be received with regret by a good many persons who have enjoyed the privilege of a late meal in them and entertaining talk with the legitimate users.

Inquiries made yesterday failed to show any real grievance in the present conditions. Alderman Everitt objects to the shelters being used to the detriment of the tradesmen who pay rates. The shelters do not pay rates, first of all because they have been provided by generous friends of the London cabmen, and because they are under the control of the charitable organisation known so the Cabmen's Shelter Fund.

It is not many years since the cabman had nowhere to go for his meals, except a neighbouring public-house. This state of things was remedied by the philanthropists, the fund was started, and drivers can now get a substantial meal at low prices while they are waiting on the ranks.

In some cases a watcher or "tout" is employed to warn them when their services are required; in a few instances the shelters are on the telephone, and during the bitter days and nights of the winter the cabmen can enjoy the comfort and cheerfulness of a well-lighted shelter, and can talk over a pipe till they are summoned by whistle or telephone.

No one denies that these shelters have been of great benefit to the cabmen themselves; the allegation that the mid-street restaurants are patronised by the public to the detriment of the ratepaying restaurateur seems ludicrously overstated.

It is precisely because our licensing laws prohibit hunger shortly after midnight that the cabmen's shelter has been hailed as a boon and blessing by many a belated man.

A hundred circumstances conspire to throw a man into London late at night or early in the morning. If he has not a club, his chances of getting a meal at a hotel, even if he books a bed which he does not mean use, are infinitesimal. He makes his way to the nearest cab rank and finds his man in a shelter aglow with light and rather stuffy with smoke. There is a smell of bacon or sausages or steak frying, and, to the weary wayfarer, it is appetising. Though he be a millionaire, he must crave for admission and food, for there is resentment of the average intruder, and if he finds the food good and the company interesting, and delays his departure for an hour or two, that is to the credit of the fast disappearing race of men whose shrewdness and humour and knowledge of London are worth understanding.

It is true that certain clubmen and night workers make a point of using cabmen's shelters for a late meal. There is one in Piccadilly known humorously as the Junior Turf Club. There are others where a privileged few can walk in with some assurance.

But there seem no good grounds for assuming that these shelters are misused in any true sense of the word. And, on Sundays, many traveller, starving by Act of Parliament, has had reason to thank his cabman for the discretion which has secured him a meal and real pleasant company."

As the 20th Century progressed, things began to change.

Firstly, cabmen switched from horse drawn cabs to motorised cabs, and, in consequence they had a much wider range of refreshment providers to choose from.

Road widening, accidents, vandalism, and even bombing in the Second World War, put paid to many of the Cabmen's Shelters, and their numbers went into serious decline.

Today, just thirteen of the little green huts survive across London, and, in many ways, they are more of a curiosity than a necessity.

So, the next time, you notice a curious green hut sitting in the middle of the street, or nestling coyly at the side of the road, you will be able to nod your head knowingly to whoever you are with, and tell them with the greatest of authority that they are looking at a true slice of London's fascinating history.